13.5 Learning and development (training)#

Organizations should support learning, innovation, and high performance to build an organization that, through individual learning, drives itself to become a “learning organization” to meet the future challenges.

Organizations that invest in their employees’ ongoing learning and development are rewarded with a more dedicated, professional and capable workforce. Organizations should encourage staff to take personal responsibility for their development, including career-enhancing opportunities across the organization. There is an expectation that managers will support and encourage employee development. The employer recognises that manager support is critical to engaging and retaining high performing staff and maintaining specialist knowledge to the advantage of the organization.

Learning and development is a mix of structured and informal activities designed to enhance knowledge acquisition and competency development in NSOs. In addition to the structured learning of online and classroom training, a range of resources and tools to support employees’ learning and development informally should also be available.

Chapter on Capability and Development, UNECE Guidelines for Managers (🔗).

13.5.1 Learning and development strategy#

Fundamental to helping people learn is an organizational culture that is supportive of learning. This requires an awareness of not only which methods are most effective, but also a robust understanding of the behavioural science of learning. The wider culture and environment of an organization impact learning, including permission to learn and support from managers and peers to implement learning.

A learning and development (L&D) strategy is an organizational strategy that articulates the workforce capabilities, skills or competencies required, and how these can be developed, to ensure a sustainable and successful organization.

A key element of an organization’s learning strategy will target all employees’ long-term development, but they may actually focus on those identified as exceptionally high-performing or high-potential individuals (sometimes defined as ‘talent’) who are critical to long-term business success. This typically includes techniques such as mentoring programmes with senior leaders, in-house development courses and project-based learning. Other organizations run a broader range of interventions to suit a broader strategy, adopting a more inclusive approach to employee development.

Learning and development strategy and policy, CIPD (2020) (🔗).

Talent management

Talent management seeks to attract, identify, develop, engage, retain and deploy individuals who are considered particularly valuable to an organization. By managing talent strategically, organizations can build a high-performance workplace, encourage a learning organization, add value to their branding agenda, and contribute to diversity management.

Wide variations exist in how the term “talent” is defined across different sectors, and organizations may prefer to adopt their own interpretations rather than accepting universal or prescribed definitions. That said, it’s helpful to start with a broad definition and, from our research, we’ve developed a working definition for both “talent” and “talent management”:

Talent consists of those individuals who can make a difference to organizational performance either through their immediate contribution or, in the longer-term, by demonstrating the highest levels of potential.

Talent management is the systematic attraction, identification, development, engagement, retention and deployment of individuals of particular value to an organization, either in view of their “high potential” for the future or because they are fulfilling business/operation-critical roles.

These interpretations underpin the importance of recognizing that it’s not sufficient simply to focus on attracting talented individuals. Developing, managing and retaining them as part of a planned strategy for talent is equally important, as well as adopting systems to measure the return on this investment.

Many organizations have recently broadened the concept, looking at “talents” among all their staff and working on ways to develop their strengths (see “inclusive versus exclusive approaches” below). At its broadest, then, the term “talent” may be used to encompass the entire workforce of an organization.

Talent management programmes can include a range of activities such as formal and informal leadership coaching and or mentoring, secondment, networking events and board-level and client experience.

Performance management and training

Learning and development opportunities aim to improve the performance of employees. Related to this, organizations engage in performance management – the activity and set of processes that aim to maintain and improve employee performance in line with an organization’s objectives. Broadly, performance management is an activity that[1]:

establishes objectives through which individuals and teams can see their part in the organization’s mission and strategy;

improves performance among employees, teams and, ultimately, organizations;

holds people to account for their performance by linking it to reward, career progression, and contracts termination.

NSOs stand to gain from a well-integrated performance management system in its HR strategy and learning and development strategy. Some country examples are provided in Box 9.

Box 9: Linking training to performance assessments - Statistics Mongolia

To encourage professional development among staff, an innovative evaluation system was introduced with assistance from the National University of Mongolia. All staff members regional and central took theoretical and practical knowledge tests in 2010. The results were kept confidential and not utilized for formal performance assessments. Again in 2011, a test was conducted, and this time the results were shared internally in NSOM. In 2012, NSOM used the following grades and points: A grade or 90-100 for high distinction; B grade or 80-89 points for distinction; C grade or 70-79 points for satisfactory; D grade or 60-69 points for poor; and F grade or 50-59 points for failure. Staff who scored less than 60, or F, did not receive bonuses in the particular year and were given time to improve their skills during working hours. In 2017, the NSOM provided opportunities to upgrade their educational level or gain a master’s degree. With the accredited University of Economics, this training is being carried out, resulting in higher academic degrees, as well as increased academic performance with NSOs and other academic institutions and improving quality.

13.5.2 Capacity development frameworks as the basis for training#

As mentioned in Chapter 13.3.4 — Competency Framework, a competency framework is a tool that guides the formulation and implementation of HR policies starting with the recruitment and aiming at building professional capability and staff well-being and ensuring that the organization stays on course in achieving the expected objectives. It is thus the framework that can guide career development and the requisite capacity development. This can be further elaborated into training skills frameworks that define the expected skills and competencies of staff in accordance with their responsibility levels and subject matter specialization. Apart from technical skills, soft skills, supervisory and management competencies also need to be addressed.

Core skills framework for Statisticians of NSOs in developing countries, SIAP (2010) (🔗);

European Statistical Training Programme (ESTP), Eurostat (2021) (🔗);

Statistical Skills for Official Statisticians, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (🔗).

In addition to individual-level capacity development, the concept of a more holistic capacity development framework that covers system, institutional and individual capacity development (termed Capacity Development 4.0, PARIS21 (🔗)) is currently being explored and applied.

13.5.3 Training topics#

General areas of training

Based on the discussions in the various chapters of this handbook, ongoing skills development is encouraged in the following general areas:

Core business of the NSO

Statistics and methodology, such as basic and advanced training on topics such as survey design and development, questionnaire design, sampling, data analysis, time series methods, non-response, imputation, quality assurance, longitudinal surveys, use of administrative records and registers and the interpretation and presentation of data.

Subject matter, such as agriculture statistics, gender statistics, System of National Accounts (SNA), business surveys, household surveys, population and housing censuses, etc.

Data, information and knowledge management (Refer to Chapter 14 - Data, Information and Knowledge Management).

People management (managing and leading others);

Project management (See Chapter 6.5.7 — Project management approaches);

General management and leadership;

Effective communication, professional relationship development and client management;

Technical expertise including IT systems and infrastructure, programming (see Chapter 15.7 — Specialist statistical processing/analytical software);

Corporate management (strategic planning and programming, people, budget, legal, financial);

Second language training (e.g., English language training);

Client service (website and data dissemination, client interactions) (see Chapter 11 - Dissemination of Official Statistics).

Skills and competencies

This section discusses the core skills and competencies needed by NSOs.

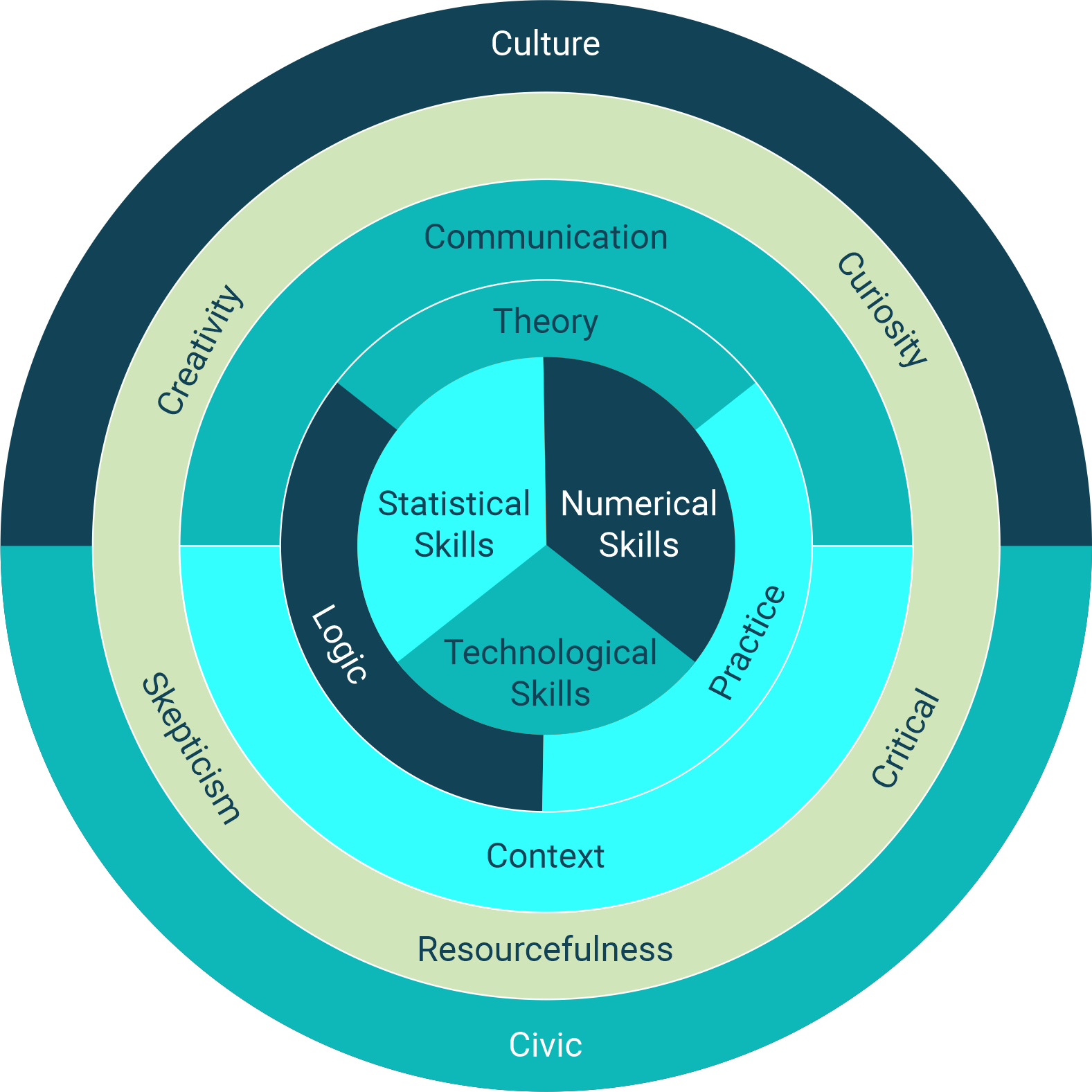

Required skills Thinking about NSOs and NSSs of the future, it is very hard to anticipate what specific skills will be required. However, three essential skills will always be required: numerical skills; statistical skills; and increasingly, technological skills.

Mathematical and numerical skills. A statistician should be able to spot patterns, understand differences between stocks and flows and be comfortable reading and writing in scientific notation.

Statistical skills Being able to work with real, often messy or incomplete data. Understanding bias; both the likely sources and what remedial actions can be taken. Statisticians should understand the subtle but important differences between accuracy and precision. They should also develop a good understanding of concepts like uncertainty and risk. A competent statistician should be able to select and use appropriate statistical techniques and models. Future technological skills are the area hardest to predict.

Technological skills Technology is changing rapidly, with consequences not only for the applications to be used but also the types of data. It will be a challenge for statistical offices to say with any certainty what will be required. If current trends have anything useful to say, then it suggests greater use of ‘freeware’ and combining packages. It also suggests a commitment to lifelong learning will be essential.

In addition, statisticians must understand the underlying logic of theory, so that having acquired skills, they can apply them and put theory into practice in a variety of real-life situations (all invariably more complex and messier than the scenarios presented in textbooks). The ability to communicate well and to present statistics in its proper context is now recognized as an essential skill for statisticians. This includes skilled application of data visualization.

Required competencies

Statisticians will need to continually update their skills over the lifetime of their career. What is less likely to change over time are the basic characteristics or competencies necessary to be a good statistician. Specifically, a statistician must be creative, curious, critical, sceptical and resourceful.

A statistician should also be aware of the cultural and civic or political environment in which they operate. A statistician must understand not only the context in which previous indicators and statistics were compiled but also the environment in which they operate. For example, when contemplating the use of Big Data, NSOs may be forced to confront issues before the law is clear or cultural norms have been established. Given the importance of public trust for an NSO, statisticians must be sensitive to these issues and understand what is acceptable by the public they serve.

Figure 16 provides a visualization of a skills and competencies framework for statisticians.

Fig. 19 Skills and competencies of a statistician

Source: Adapted from MacFeely, 2019#

Preparation for a career as an official statistician, Steve MacFeely (2019) (🔗).

“Traditional” skills and competencies: Survey data process

The survey data process requires staff with specific skills and competencies (see Chapter 9.2.9 — Survey staff training and expertise) as follows:

Survey managers;

Subject matter specialists;

Methodologists;

Data collection and follow-up specialists;

Data capture, verification and editing process;

Interviewers;

Data entry and editing clerks.

“New” skills and competencies: Accessing and use of Big Data

Accessing and using Big Data is an area where NSOs have developed new skill sets and competencies in recent years. A discussion on what this entails in terms of training and development of NSO staff can be found in New data sources for official statistics – access, use and new skills, UNECE (2019) (🔗).

A multifaceted transformation of national statistical systems is needed to meet the new data innovation challenges and to reap benefits from using Big Data. Existing capacity building programmes should be broadened and possibly be focused on transforming the technology architecture and the workforce, exploiting more Big Data sources and redirecting products and services. The transformation of the technology architecture should facilitate the shift from physical information technology equipment on-site towards introducing a cloud-computing environment along with the adoption of common services and application architecture for data collection, registers, metadata and data management, analysis and dissemination.

This approach should be accompanied by capacity-building programmes that support the progressive diversification of the new skill sets of the national statistical systems’ staff. These programmes should range from data scientists and data engineers using new multisource data and modern technology, through lawyers strengthening the legal environment, to managers leading the change in corporate culture with a continuously improving quality standard. Those new capabilities should allow for adopting a standardized corporate business architecture that is flexible and adaptable to emerging demands. They should also be process-based rather than product-based, with increasing use of administrative and Big Data sources for multiple statistical outputs. In addition, our dissemination and communication strategy should be upgraded and made adaptable to target different segments of users by applying a diverse set of data dissemination techniques, including mobile device applications and data visualization of key findings.

Related: Big data team level competency, UNECE (2016) (🔗).

13.5.4 Training modalities, including learning in the workplace#

Training may be in the classroom or self-paced through online courses, allowing managers and staff to organize learning in line with work priorities and ensuring that all staff members have training opportunities.

There has been much discussion on the merits of utilising information technology for delivery of training through online or web-based e-learning courses. E-Learning courses are cost-efficient and can reach a larger number of participants. Webinars are useful for short seminars on specific topics. NSOs should develop a strategy for online learning activities that takes into account the IT infrastructure needs. Inadequate IT infrastructure is one of the main reasons the uptake of web-based learning activities is difficult for many NSOs. The statistical community could work together to make available online learning resources such as through wikis and common shared platforms for e-learning.

Managers can be effective coaches in the workplace to support training with:

one-to-one guidance;

sharing workplace experience;

sharing technical expertise;

effective performance feedback to sharpen staff skills and improve their performance.

Managers can also invest in having their most experienced employees take part in coaching and mentoring programs. It may also be useful to have a team of coaches and mentors who can support newly recruited and less experienced employees. Mentoring encourages sharing knowledge, providing guidance and advice about work and the workplace and discussing career development.

Box 10: Examples from Statistics Poland

Knowledge sharing. In Statistics Poland, there is a practice that after a foreign training (e.g., within the European Statistical Training Programme), participants are obliged to share their knowledge by conducting internal training. The course is held in Statistics Poland or in the Regional Statistical Office. The rest of Polish Official statistics units can participate in the training via videoconference.

Internal coach programme. The Internal Coach Programme aims to improve knowledge transfer between employees, which is a key element of the organization’s development. It also allows incorporating in Statistics Poland and Regional Statistical Offices the concept of a learning organization adapted to rapidly changing conditions. Trainers from the same organization know the needs of training participants perfectly. Thanks to the Programme, it is possible to educate professional trainers inside the organization who effectively contribute to raising the staff’s professional competence. Internal trainers conduct mainly specialist training, including statistical research and statistical analysis, as well as support the professional development of employees, e.g., a group of interviewers.

Managers can provide on-the-job training and development as part of the regular working environment. For example, holding information sessions when a person returns from training to share what they learned (“re-echoing”) can be beneficial. It is also useful to ‘buddy up’ team members to share knowledge and skills. This is also effective in maintaining work program continuity if an employee is absent from the workplace for a period of time, leaves the workgroup, or the organization. A “brown bag” seminar - an informal meeting that occurs in the workplace generally around lunchtime - is also informal a good way of sharing knowledge. Some examples from Statistics Poland are articulated in Box 10.

Developing Talent Management Plans (🔗), the example from Statistics Canada.

13.5.5 General purpose training cycle#

While there are different ways to provide career-long training, one way that has proved to work in many countries is to consider general-purpose training as having three distinct cycles:

Introductory cycle

This is primarily designed for newly recruited staff. Its purpose is to ensure their speedy integration into the organization, which implies both becoming familiar with the traditions of the statistical organization and being able to contribute in any of the domains or functions within its scope. Virtually all agencies administer such training, even if they do so in the most informal manner.

Intermediate cycle

This training cycle is designed primarily for those who have worked in a statistical organization for a period of five to ten years and who have not had an opportunity to refresh their skills.

Administrative cycle

Throughout a staff member’s career, its direction eventually becomes foreseeable. Those who can fill policy-making positions within their respective agencies should be trained in the subjects that will demand their energies once they reach management levels. These subjects include financial administration and control, large project management, marketing, the institutional set-up of the Government, and other external features to the statistical organization.

Moreover, one should make the corresponding cost part of the organization’s regular budget and administer training to all targeted staff members as a matter of course. It would be especially critical to pay attention to staff development during times of budget cuts applied to the NSO, as often, maintenance of premises and training (whether in-country or overseas) are the first budget line items to suffer during times of reduced allocations to the NSO.

13.5.6 Specific situations#

Training of employees with no university education

There are several NSOs where a large number of staff lack university education. In this situation, training programmes for them are particularly important to enable them to better carry out their tasks. In addition to the introductory courses for new employees, more extensive courses may be useful when they have acquired enough statistical work experience. The topics may focus on more advanced aspects of statistical production. Such systematic training in important day-to-day operations cannot be over-emphasized.

In addition, voluntary and more advanced courses may be arranged for employees who have demonstrated high learning capacity and are motivated to improve their qualifications. Courses may be given in basic theory on sampling, demography, economics, coupled with exercises designed to build bridges between theory and application. Experience has shown that after attending such courses, employees have been able to carry out work that previously would have been assigned to professionals with higher education. Thus, the latter personnel, who play a very significant role in a statistical agency and often are scarce– particularly in developing countries– can be released for jobs requiring higher qualifications.

Training on leadership and management

Leadership and management capabilities are integral to meeting NSO goals, encouraging innovation and high performance, and building a sustainable future. Individuals with leadership aspirations need to build this capability and be responsible for their own learning. In many cases, staff with primarily technical backgrounds are placed in positions of management and administration.

As part of succession planning, NSOs need to offer project management and leadership training to interested staff. Many future managers can be selected from trained staff members. This also supports career development. Leadership training should be a requirement for all supervisors; either before or during their assignment.

13.5.7 Beyond general-purpose training- Where to obtain training#

General-purpose or basic and introductory training for NSO staff is not sufficient. It needs to be complemented by more specialised defined courses to meet specific needs. Many offices are not in a position to provide courses at all or at any of these levels. Therefore, alternatives and special arrangements are so important.

In-house and national public administration training centres

Many NSOs will have at least general-purpose training for statistics as a function of its human resource department. Training on administration, management, and leadership is also available (and in some countries required for certain high-level positions) from a national public administration training centre. Some NSOs have an academic institute (e.g., Indonesia-STIS, India-ISI and France-ENSAE) that confer formal diploma or bachelors-level degrees in statistics. Increasingly, NSOs or NSSs are establishing a statistical (research) and training institute. The institute provides specialised training on statistics not just for the statistical agencies but also for other government agencies’ needs. In some cases, the statistical training institute also offers courses to countries in the region (e.g., Statistics Korea, India Statistical Institute). In some cases, the Government may take over the NSO Training Institute and incorporate it into the formal educational system (e.g., Suriname).

Regional training institutes

Some regions have established intergovernmental regional training institutes that provide both general-purpose training and specialised training courses. The offerings use mixed modalities - regional face-to-face/online courses and country-focused courses. Some institutes offer “scholarships” to participants (e.g., the JICA-funded 4-month and 6 to 8-week courses at the Chiba premises of the Statistical Institute for Asia and the Pacific).

The list of regional and global training institutes members of Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST) is available here.

Role of regional training networks

In recent years, training institutes of NSOs and other training providers in a region have created a regional network to facilitate the sharing of resources and information on training developments and design common curricula for selected areas.

Network for the Coordination of Statistical Training in Asia and the Pacific, SIAP (🔗).

Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training

The Global Network of Institutions for Statistical Training (GIST) is a network of international and regional training institutions that build sustainable statistical capacities through efficient, effective, and harmonized delivery of training established by the UN Statistical Commission. The overarching goal of GIST is to build sustainable statistical capacities through efficient, effective, and harmonized delivery of training at global and regional levels. GIST aims to achieve this goal by facilitating collaboration, coordination, and outreach among key providers of statistical training at the regional and international levels.