8.5 Designing and developing a quality management framework#

An NSO has to develop a quality management framework appropriate to its unique situation as defined by the legislation that it enacts, its mission, vision, core values and strategic objectives, demands from users and stakeholders, criticisms regarding lack or relevance or timeliness or publication errors, and so on. However, although these may well vary from one country to another, there is no point in completely re-inventing the wheel in designing an appropriate framework. Rather than start from scratch, it is easier and more effective to select general quality management principles from those described in Chapter 8.2 — Generic quality management systems and other relevant standards and a quality assurance framework, guidelines and tools from those described in Chapter 8.3 — Quality assurance frameworks, guidelines, and tools, customise them as needed, and use them as the starting point for framework design and development or revision and implementation.

The starting points for development are the existing quality framework (if any), the regional quality framework, and the UN NQAF Manual.

Of course, the NSO should also take advantage of quality tools, wherever developed. For example, an NSO in an EU Member State will inevitably base its framework on the ES CoP, the ESS Quality Assurance Framework and accompanying tools.

8.5.1 Organizational context#

A prerequisite for a quality management framework is an understanding of the organizational context within which the framework will operate.

This includes the NSO vision, mission, core values, and strategic objectives. Assuming that these are aligned with the UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, they are not to be questioned, but rather to be reviewed and understood as the base on which to build the quality management framework.

The next step is to identify the particular reasons for, and objectives of, quality management within the NSO and the benefits that are expected to be derived from it.

Many of these may be shared with other NSOs; some may be unique to the organization.

Published errors that caused embarrassment and potential damage to the credibility of the organization and its outputs may be a catalyst or large changes in resources may be the impetus for the shift towards managing quality in a more formalized and systematic way. Similarly, government-wide reform initiatives, changes in NSO management, NSO restructuring, or the need to comply with legislation or regulations are examples of other driving forces leading to a decision to embark upon the formulation of a quality assurance framework. Statistics Canada’s first quality assurance framework arose from the need to provide evidence to an externally imposed government audit.

As noted in the UN NQAF Manual, the process of developing a quality management framework is typically best carried out by an NSO task force comprising experts from a variety of areas, for example: programme planning; survey design; survey operations; dissemination; infrastructure development and support.

The framework development process has intrinsic benefits of its own since it obliges staff from various disciplines to come together to confront and tackle quality issues, to think through the requirements, to agree upon priorities, and to evaluate the costs and benefits while keeping in mind that not everything can or should be undertaken.

8.5.2 Quality concepts#

General quality management principles

Underpinning a quality management framework is a set of general quality management principles.

Regarding a choice of such principles, there seems to be every reason to adopt one of the formulations associated with the generic quality management systems summarised in Chapter 8.2 — Generic quality management systems and other relevant standards. The ISO 9000 general quality management principles are probably the most common choice. However, an NSO in a European country may well opt for those associated with the EFQM Excellence Model, especially if that is the preferred option for other government agencies in the country.

Of course, an NSO can mix and match principles from two or more generic systems, or it can invent its own from scratch. There seems little point in doing this. Each of the various generic systems has been carefully thought through and is supported by implementation guidelines and a body of experience.

The major decision is whether to build general quality management principles into the quality assurance framework or to introduce a separate generic quality management system into the NSO. In essence, the answer depends upon whether the organization wants to seek quality certification. For example, it may be a government prerogative that all government agencies in the country seek quality certification.

If the organization decides to seek certification, then it is imperative to have a quality management system based on standards that provides certification. It can be selected from amongst the options presented in Chapter 8.2 — Generic quality management systems and other relevant standards.

If the organization decides that certification is not necessary, then it is preferable to design a quality assurance framework that includes general quality management principles rather than to have a separate quality management system.

Defining/adopting statistical quality principles and associated indicators

At the core of a quality management framework is the definition of quality and a set of statistical principles and corresponding elements/indicators.

Whilst an NSO may choose its own particular definition and set of principles, again, there is no great virtue in reinventing the wheel. The sets of principles outlined in Chapter 8.3 — Quality assurance frameworks, guidelines, and tools are a good starting point. In the absence of any particular reason to the contrary, there is a lot to be said for defining the quality principles in accordance with the principles in UN NQAF, or the ES CoP or other regional framework. These frameworks have very similar coverage.

If alignment with the IMF DQAF is important for an organization, then the DQAF can be used as it stands, or in a hybrid form with the ES CoP as, for example, in the case of Statistics South Africa’s SASQAF, summarised in Chapter 8.4.5 — South African Statistical Quality Assurance Framework.

8.5.3 Instilling a quality culture#

As noted in the UN NQAF Manual, quality assurance activities – monitoring, documenting, standardizing and reporting in particular – are time-consuming and labour intensive, with payoffs that are not immediately obvious.

Thus, staff reluctance to accept an increase in their workload associated with the introduction of a quality framework and no corresponding increase in resources to carry out their “regular” responsibilities has to be overcome. Furthermore, quality work has to be reviewed, maintained and enhanced over time, which requires a long-term commitment, not only from management and the quality team but from the staff at all levels. To obtain this commitment, the promotion and communication of the quality management features, benefits and requirements are necessary. This can be accomplished through sharing of information and training, both of which should be tailored to the various levels of staff. The NSO must publicise quality principles, explain how they are to be implemented and what the impacts are likely to be. Quality must become a core value, embedded in the culture of the organization.

The main tool is quality training. Development and implementation of a quality training programme is essential. It may well be in two parts.

The first part focuses on general quality management principles and their application in the organization. Such training can readily be purchased from a reputable management consulting company. It is likely to be one of their standard offerings. Provided the company is supplied with appropriate documentation about the NSO, it will most likely be prepared to illustrate the application of the principles with concrete examples from the NSO itself.

The second part focuses on statistical aspects of the quality management framework – the statistical quality assurance framework – incorporating the definition of quality, the statistical quality principles and the quality tools to support their implementation. Such training is specialised to NSOs and thus has to be developed in house or borrowed from another NSO or international statistical organization.

8.5.4 Developing guidelines on statistical quality#

Quality guidelines are a vital aspect of a quality management framework. They provide quality-related practices and reference material that support the application of the statistical quality principles. The starting point for developing quality guidelines for an organization are the sets of quality principles, indicators/elements and guidelines that have already been developed. These include:

The quality principles, requirements and elements in the UN NQAF Manual

The quality principles, indicators and methods in the ESS Quality Assurance Framework (🔗), which accompanies the ES CoP

The dimensions, elements and indicators in the IMF’s Data Quality Assessment Framework (DQAF)

The various country QAFs summarised in Chapter 8.3 — Quality assurance frameworks, guidelines, and tools, and available from the corresponding websites

In all cases, the guidelines must be tailored to the specific situation of the organization as they need to take into account the legislation, statistical infrastructure, skills and resources that are particular to the organization and the country in which it operates.

Quality guidelines may be principle oriented, or process-oriented, or a mixture, as further discussed in the following subsections.

Quality principle-oriented guidelines

Quality principle-oriented guidelines are organized around the quality principles. They provide advice, tools and reference documents for each of the indicators/elements associated with the principles. The ESS Quality Assurance Framework and the UN NQAF are examples.

The virtue of a principle-orientation is that the guidelines can be very readily converted into a quality checklist (as further described below) that is aligned with the output quality principles that are the basis for a user quality report.

The disadvantage relative to process-oriented guidelines is that they are not so readily applicable to process design, development, production and evaluation.

Process-oriented guidelines

Process-oriented guidelines are organized around the phases of a generic statistical process, preferably as defined by the Generic Statistical Business Process Model (GSBPM v5.1). As statistical infrastructure and cross-cutting activities such as programme design, classification management and metadata management are not effectively covered by the GSBPM, the set of process phases has to be supplemented by groups of activities such as professional independence, transparency, coordination of the NSS, management of statistical standards and metadata management to provide a complete set of headings for the guidelines.

The advantage of process-oriented guidelines is that they can be readily applied during process design, execution and evaluation. The disadvantage is that they do not so readily lead to quality evaluation from a user perspective as they do not align with the output quality principles.

Mixture of quality principle and process-oriented guidelines

Istat’s Quality Guidelines for Statistical Processes (🔗) are an example of a mixture of quality principle and process-oriented guidelines. As noted in Chapter 8.3 — Quality assurance frameworks, guidelines, and tools, they are in two parts.

The first part is dedicated to process quality and follows the phases of the statistical production process.

The second part concerns output quality, with some output quality measures actually coming from the first part.

8.5.5 Quality monitoring and evaluation overview#

It is important to have an overall strategy for quality monitoring and evaluation of statistical processes and their outputs to ensure that all aspects are covered. Note that in this context, quality evaluation, quality review and quality assessment are regarded as synonyms and for brevity are referred to simply as evaluation, as this is the term used in the GSBPM.

Evaluation is undertaken after a statistical process has been completed, in contrast to monitoring which is undertaken as the process takes place. Evaluation is much more in-depth than monitoring. It typically covers several cycles of a monthly or quarterly process, whereas monitoring takes place during the course of each cycle.

Six types of quality monitoring and evaluation of a process may be distinguished. They are:

monitoring of quality and performance indicators during each cycle of the process;

application of quality gates during each cycle of the process;

self-evaluation of the process, typically annually;

internal, peer-based evaluation of the process on a rotating or as-needed basis;

external evaluation of the process, on an as-needed basis;

labelling of process outputs as official statistics, once only, or with periodic renewal.

Figure 9 indicates how these types relate to one another and to the development, conduct and enhancement of a statistical process.

Fig. 9 Relationships of monitoring, evaluation and labelling#

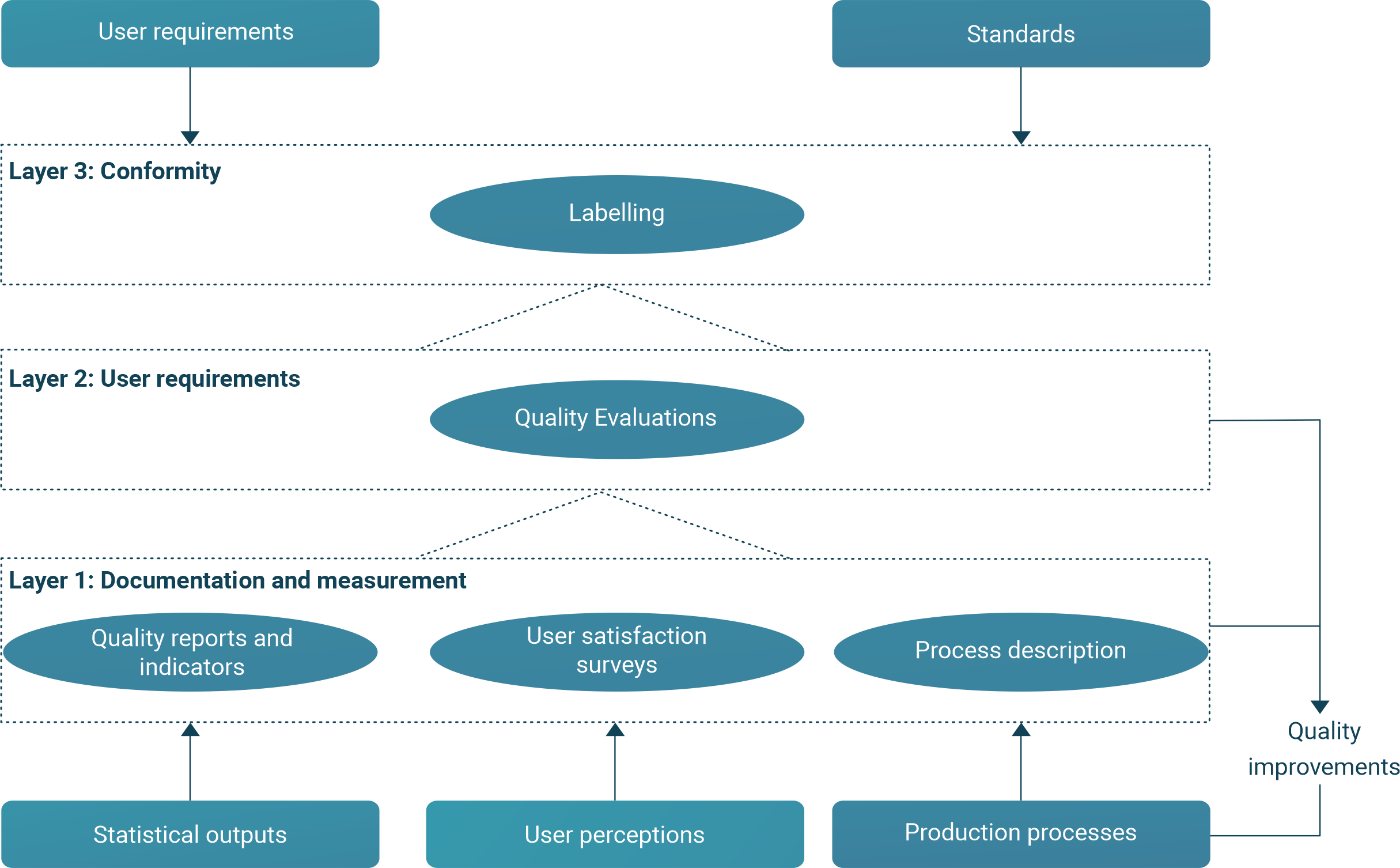

A slightly different perspective is presented in Figure 10, which shows Eurostat’s approach to quality assurance. Monitoring and evaluation are represented by three layers. Layer 1 is at the level of the process manager. On the way from Layer 1 to Layer 3, information about process quality is increasingly summarised, making it more appropriate for senior managers and users.

In developing countries, resources may limit the scope of monitoring and evaluation of the elements in Layer 1.

Fig. 10 ESS monitoring, evaluation and labelling#

8.5.6 Monitoring quality and applying quality gates#

Quality and performance indicators

The objectives of identifying and monitoring quality and performance indicators (sometimes referred to as key performance indicators) are to check ongoing operations as they take place in order to:

monitor quality (i.e., effectiveness) with respect to target objectives, identify sources of operational errors and correct them; and

monitor performance (i.e., efficiency) with respect to target objectives, identify sources of operational blockages and correct them.

Quality and performance indicators may relate to the statistical process or to its outputs. They should be very carefully chosen as their main purpose is to monitor the process in real-time. Too few quality and performance indicators, or the absence of quality and performance indicators covering key aspects of the process, results in ineffective monitoring. Too many quality and performance indicators, or ill-chosen ones, burden the process and waste resources.

The procedures involved in the development and use of quality and performance indicators are to:

define a suitable set of indicators based on a generic list;

designate selected indicators as being key and set targets for each of these;

monitor the values of quality and performance indicators and act on operational problems;

analyse the values of key quality and performance indicators on a regular basis and compare the values with targets;

take action to address operational problems thereby identified; and

document structural problems, i.e., problems that cannot be solved at the operational level, and provide them as input to the next quality evaluation.

Examples of generic quality indicators are i) response rates by stratum; ii) sampling errors by stratum; iii) error rates during data capture and primary editing; iv) number of outliers detected during secondary editing/analysis; and v) the number of days after the reference period that data are published.

Examples of generic performance indicators are the average time required by a respondent to complete a questionnaire; the number of unsuccessful follow-up attempts, and the number of staff days required to complete editing.

The ESS maintains a standard set of Quality and Performance Indicators (🔗).

Quality Indicators for the GSBPM Version 2.0 (🔗) provides indicators to monitor the quality of the production processes for each phase.

Quality gates

The objectives of quality gates are to ensure significant errors are detected as soon as possible after they have occurred, for the underlying causes to be determined, for the errors to be corrected, and (in the case of a repeating process) for the process to be adjusted to prevent or reduce similar errors in the next cycle. They are, in essence, quality control.

Quality gates are placed at key points in the process. To identify appropriate key points, it is necessary to consider what can go wrong, when it can occur, what impact it can have, and how it can be detected. To facilitate detection, quality gates are typically placed at natural beginnings or endings of sub-processes within a process. For example, after sample selection, but before data collection. This is essentially risk management.

Problems uncovered by quality gates are addressed at the time that they are discovered. The action taken can vary from stopping the process entirely until the underlying problem is fixed to delaying the process, to proceeding with caution.

Examples of quality gates for a statistical production process are:

data collection does not commence until the sample has been verified;

data collection is not closed off until an acceptable response rate has been obtained;

statistical tables and commentary are not released until they are verified and signed-off by the head or a deputy head of the organization.

Quality dashboard for senior management

The aim of a dashboard is to provide senior management with a monthly/quarterly review of ongoing statistical operations, thereby enabling:

overall monitoring of quality and performance with respect to target objectives;

identification of areas of generally poor quality or performance.

This encourages and facilitates decisions regarding short-term changes that are needed.