5.3 Layers of national data ecosystems#

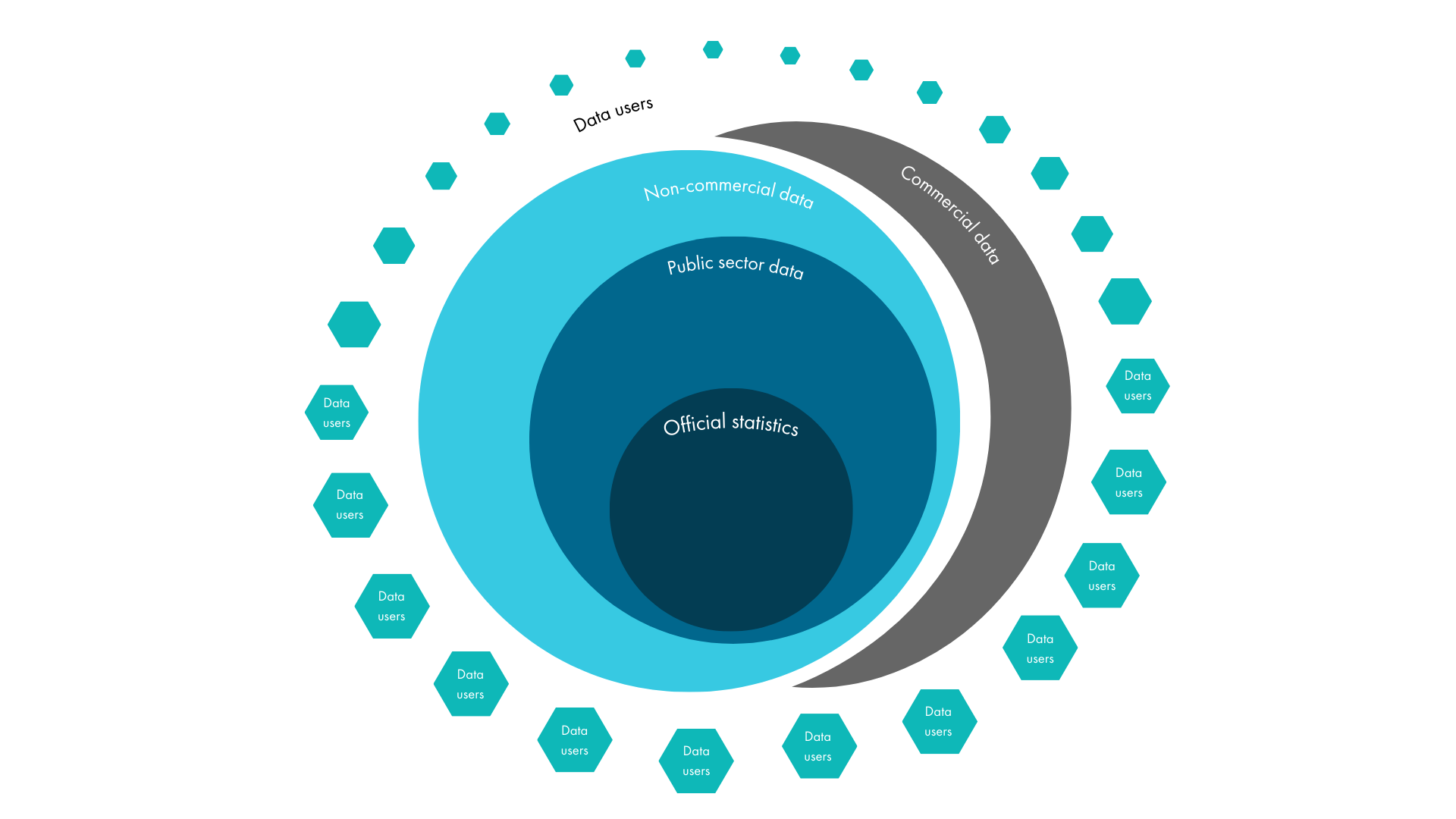

The working definitions in the previous section highlights that national data ecosystems are multi-layered and comprise many players (or stakeholders). One way to visualise this is through a diagram that has evolved through several discussions of data ecosystems, and attempts to show the view of the national data ecosystem from the desk of a senior manager in an NSO. The diagram below (Figure 4) is referred to as the “onion model” because it illustrates the layers of the national data ecosystem radiating outward from the “core” of official statistics. The larger outer layers encompass the smaller inner layers, but the diagram does not depict the interactions and interlinkages between them.

Fig. 4 Onion model#

Official statistics are defined in the previous section, and this part of the national data ecosystem is also known as the National Statistical System (NSS), comprising the NSO and other producers of official statistics (sometimes called “other national authorities”). This is the part of the national data ecosystem where it is usually easiest for senior managers of national statistical offices to exert influence. Modern statistical legislation will define the NSS, and often include some provisions for governance mechanisms such as a governing council, as well as practical measures such as standard methods, classifications and quality frameworks.

Looking beyond the relatively safe perimeter of official statistics, the next layer comprises public sector data, usually referred to as administrative data. All branches and layers of government need data to function, to help them allocate their budget to different activities, to administer regulations, as well as to evaluate results. This is the “evidence” needed for evidence-based policy making. Some of these data sets are of direct interest for producing official statistics, and the issues around access and use of administrative data for statistical purposes are comprehensively covered in Chapter 9.3 — Administrative sources. However, there is a wider value to society in considering data and metadata (see Chapter 11.4 – Metadata - providing information on the properties of statistical data)(including quality) standards for public sector data that are not (yet) of interest for official statistics, to support greater interoperability for a wide range of uses. The main challenge is that each public sector data holder is usually focused on a specific administrative use for each data set, and therefore has limited interest in standardising with others. To get around this, some countries have developed government-wide data strategies. Where this happens, it is important that the national statistical office takes a proactive role, promoting the use of statistical standards, classifications and good practices wherever possible, to facilitate statistical use of public secto data, including administrative data.

Between the public and private (commercial) sectors, there is a layer of non-commercial data stakeholders, typically including academics, researchers and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). They are typically looking for data to answer specific research questions, and sometimes resort to direct data collection themselves. They are therefore mainly users of statistical and other government data (when they have access), but can also be data suppliers, as well as partners in the development of new data sets, methodologies and analyses. This layer can also include non-commercial groups that facilitate the generation of structured data by citizens, for example weather observations or wildlife sightings.

The next layer is the rapidly growing commercial data industry. They realise the commercial value of data, and are often prepared to trade data in a similar way to oil or other commodities. They are also increasingly realising the value of extracting insights from data, so are becoming more focused on analytic techniques, including the use of artificial intelligence. They collect or generate data, including by integration of other sources, if they think that could generate an income. They may provide platforms for citizens and/or businesses to interact, whilst building data-based profiles of those citizens or businesses, which can be used or sold for marketing purposes. This layer is generally only interested in collaboration with official statistics if they gain in some way from that collaboration. For example, they may be interested in using statistical standards and classifications if that improves data quality or interoperability, or they may be interested in collaborating in specific areas of research. If there is no obvious benefit for them, they usually have to be compelled (e.g. by statistical legislation) or compensated (e.g. by payments) to share data with official statistics bodies. An additional complication when dealing with this layer is the need to avoid giving actual or perceived benefits to certain companies and not others, as this can open the door to claims that the statistical office is distorting the data market and applying favouritism.

The final layer (data users) of the model can be described, in classification terms, as other data actors “not elsewhere classified”. It mainly comprises providers and users of data who don’t fit into any of the other layers, including the general public. Their needs are extremely diverse, and often rather specialised and/or localised. It is impossible to engage with all of them, let alone meet their needs, but partnerships with data intermediaries, such as news organisations and data journalists, can help to reach some in this layer.

In Figure 5 below, the onion model is extended to illustrate specific types of actors within each layer, as described above.

Fig. 5 Onion model with types of actors and data#

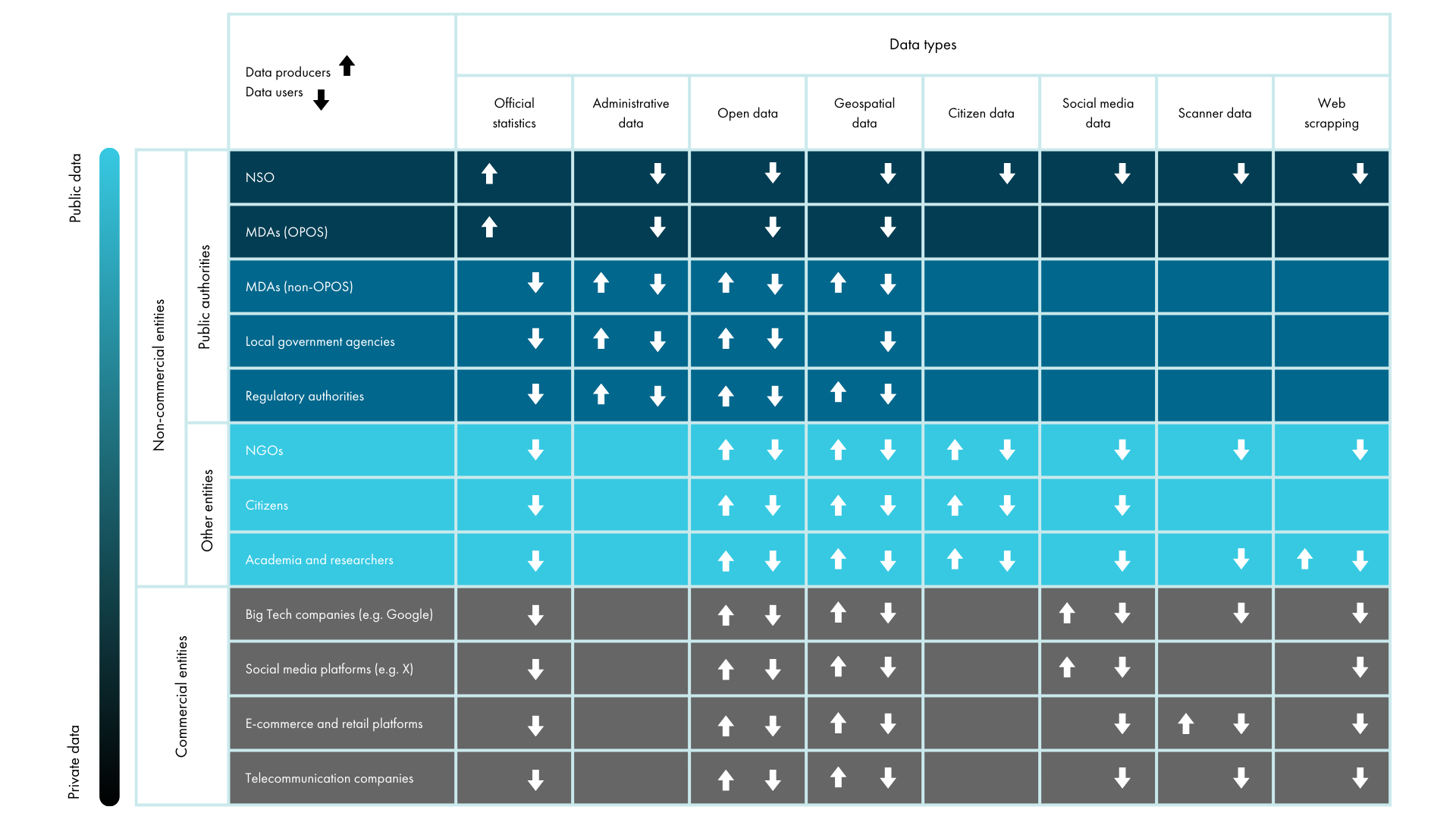

Figure 6 below further illustrates the data streams and interactions among different data producers and types of data. An upward-pointing arrow (↑) represents the role of actors as data producers, while a downward-pointing arrow (↓) indicates their role as data users.

Fig. 6 Data producers and types of data#

Another possible extension of the model could be to consider the interaction of different regulatory frameworks. For example, data protection legislation will typically apply to all layers of the model, whereas statistical legislation mostly impacts the official statistics layer, and only touches the actors in the other layers when they have a legal obligation to provide data.